Get full access with a free account

Benefits of the Coloplast® Professional Educational platform

- Full access to educational content, events and resources

- Track your progress

- Share content with your colleagues

- Share supporting material with your patient

Understanding skin tears

What is a skin tear?

A skin tear is a traumatic wound that is caused by a mechanical force. The mechanical force could be shear or friction, or it could be the result of removing an adherent dressing.1

Skin tears can lead to partial or full separation of the skin’s outer layers (epidermis and dermis). They can also lead to a separation of both the epidermis and the dermis from the underlying structures (a full-thickness wound). The severity of a skin tear varies, depending on the depth of the wound. However, skin tears do not extend through the subcutaneous layer of the skin.1

They can occur on any part of the body, but are most common on the hands, arms and legs.1

Who are at risk of getting a skin tear?

Our skin is the body’s first line of defence. It acts as a protective barrier, and prevents damage to our internal tissues and organs. However, if our skin becomes frail or fragile, it’s more likely to be damaged. This increases the risk of skin tears, as less force is needed to cause a traumatic injury.2

While skin tears can happen in a variety of patients, the elderly population is particularly at risk. As we age, our skin becomes more fragile. The skin’s ability to heal itself slows down, which can make it even more vulnerable to skin tears.2

If an elderly patient needs help to carry out daily tasks, such as moving around or washing, this can increase the risk of skin tears. Additionally, elderly patients who have other illnesses, are undergoing certain medical treatments (e.g. chemotherapy) or are on certain medications (e.g. steroids), can have an even higher risk of developing skin tears.1

How do I prevent skin tears in my patient?

To prevent your patient from getting a skin tear, you can take two steps. One, find out if your patient is at risk. And two, take steps to minimise your patient’s risk. Let’s look at two tools that can help you to do this.

Tool #1: The Skin Tear Risk Assessment Protocol

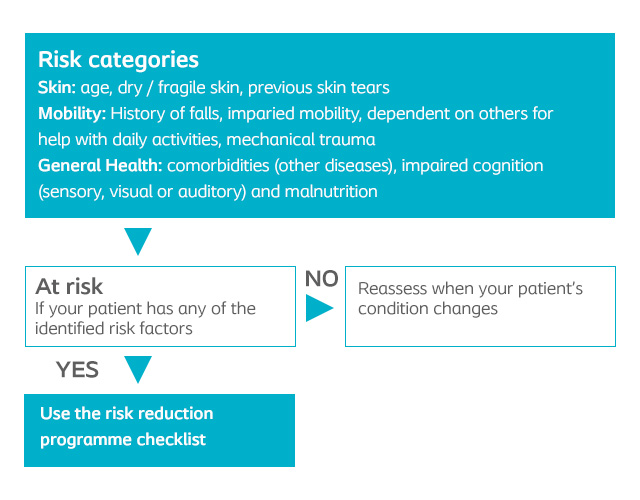

To find out if your patient is at risk, you can use the Skin Tear Risk Assessment Protocol (See Figure 2).1

This protocol looks at three main risk factors:

- skin,

- mobility, and

- general health.

Figure 2: Skin Tear Risk Assessment Protocol1

Tool #2: The Risk Reduction Programme Checklist

If you find out that your patient is at risk, use the Risk Reduction Programme Checklist (See Table 2). This will help you protect your patient from skin tears. The checklist gives you a list of tips and suggestions based on the same three factors as the risk assessment: skin, mobility and general health. By controlling the risk factors around your patient, you can help them maintain skin health and avoid injury.1

| Risk factor | What you should do |

|---|---|

|

Skin |

|

|

Mobility |

|

|

General health |

|

The skin and it's function

It is essential to know the structure of the skin to assess and manage wounds.8 It provides a semi-permeable barrier that protects the body from the external environment and maintains homeostasis in the body.19,35

The skin consist of three layers:

- The epidermis - traps moisture19

- The dermis - functionality due to the variety of structures8

- The subcutaneous tissue - insulation and cushions35

How to treat skin tears

This section provides further insight into:

- how to treat skin tears

- how to choose the right skin dressing

Understanding the skin layers

The Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost, visible part of the skin.19. It is a highly specialised structure that adapts to environmental conditions.19,28

It provides a physical and chemical barrier to block entry of foreign substances and triggers an immunological response against any pathogens that penetrate the barrier.19,28

It has a thin layer of cells varying in thickness from 0.05 mm on the eyelids to 1.5 mm on the palms and soles.8

Function of the epidermis:19

- Barrier function

- Control of water loss

Protection against UV light, bacteria and allergens

The Dermis

The dermis is the middle layer of the skin and is approximately 15-40 times thicker than the epidermis.4,35

The dermis consist of connective tissue. A semi-fluid substance mainly consisting of collagen and elastin fibres.4,35

The dermis contains:

- Nerve endings

- Blood vessels

- Skin appendages (e.g. hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands)4,35

The Subcutaneous Tissue

The subcutaneous tissue (subcutis) is the lower layer of the skin between the dermis and fascia.35

Subcutaneous fatty tissue can often be visible in the base of deep wounds such as pressure ulcers or traumatic wounds.5

Functions of the subcutis include:35

- Insulation

- Cushions

- Retains moisture

Did you know?

- The skin is the largest organ in the body 10,35

- The skin renews itself every 28 days.36

- The thickest skin is on the feet, at 1,5 mm thick.8

- Every minute 30,000 dead skin cells are shed. 9

The lipids produced in the outer layer of the skin are crucial to the function of the epidermal barrier. The lipid barrier can easily be disrupted by soaps and detergents.19

The average person’s skin when stretched can cover 2 square metres and contain more than 11 miles of blood vessels.34

Skin has its own community of microorganisms called skin flora. Its density and composition varies with anatomical location and can be 1000s per square metre.34

Factors affecting the skin barrier function

Factors influencing the skin barrier function:

- The effects of ageing / Elderly skin

- Neonates

- pH levels of the skin

- Dry skin

- Moisture

- Moisture Associated Skin Damage (MASD)

|

The effects of ageing |

Neonates | Moisture | Dry skin |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Elderly skin has fewer sebaceous glands resulting in reduced secretion of natural lipids, increasing the need to moisturise.2,29 Elderly skin develops a flattening of the rete ridges that hold the epidermis and dermis together resulting in the higher incidence of skin tears in the elderly.29 |

Premature babies have fragile, thinner, more immature skin than full term babies, resulting in higher Trans Epidermal Water Loss.19 The skin of full-term babies contains 10-20 layers of stratum corneum. Premature babies only have 2-3 layers.17 The overall result is that preterm babies are more prone to skin trauma from adhesive dressings and tapes and localised pressure from IV lines and tubing.19 |

The term ‘moisture-associated skin damage’ (MASD) is used to describe all types of skin damage caused by moisture.21 Damage to the skin caused by moisture has a significant impact, decreasing the skin’s ability to act as a functional protective barrier.21 |

When the skin becomes dry, the superficial corneocytes on the surface attached to the deeper keratinocytes, pile up and become visible as scaly, rough and flaky skin.15 When skin is dry, the function of the acid mantle is reduced resulting in reduced protection against bacteria. This, together with minor trauma from scratching, increases the risk of skin infection.31 |

Moisture balance is imperative to wound healing

If exudate is not properly managed the periwound skin may become macerated.39

Macerated skin has a higher pH than normal skin and increases the risk of bacterial and fungal infections, such as Candida albicans. 4,19

It is important that excess exudate is removed from the wound by an absorbent dressing with the ability to contain exudate under pressure.1

MASD - moisture associated skin damage

Chronic wound fluid

Chronic wound exudate is rich in: 1

- Growth factors that which promote healing

- Dead white cells, bacteria, high levels of inflammatory mediators and proteases which can disrupt the normal wound healing process

High protease content of chronic wound fluid causes maceration and breaks down of the stratum corneum.19,39

Failure to manage exudate adequately can lead to exposure of the periwound skin to moisture resulting in maceration of the periwound skin.39

Intertriginous dermatitis (ITD)

ITD is an inflammatory dermatosis occurring as a consequence of moisture, friction and bacteria trapped between two skin surfaces.6

In skin folds, there is a risk that sweat can get trapped leading to build-up of moisture and when the skin rubs together it becomes painful due to skin excoriation. 37

This increases the risk of secondary infection by fungi and bacteria and leads to intertrigo.37

Peri-stomal moisture-associated dermatitis

Peri-stomal skin damage occurs when skin is exposed to effluent from an ostomy, resulting in inflammation and erosion.38

Lipases and proteases produced by faecal bacteria break down protein in keratinocytes, contributing to skin breakdown.6

Incontinence Associated Dermatitis

Incontinence Associated Dermatitis (IAD) is a complex mechanism that is not fully understood but involves an interaction between, urine and faeces on the skin, humidity, mechanical irritants and frequent use of soap and water.19

If the skin is exposed to urine, faeces and detergents for a longer time the skin pH becomes more alkaline disturbing the acid mantle and increasing skin damage.19

Diagnosing the cause of skin barrier damage

In the sacral area, even experts have difficulty identifying if skin damage is due to pressure damage or moisture damage.22

An example is patients who are at risk for IAD. They are also at risk for pressure ulcer development, due to impaired tolerance to friction and sheer when IAD is present.6

Stage I pressure ulcers are often mistaken for mild/moderate IAD as both conditions present as erythema of intact skin.6,19

You may also be interested in

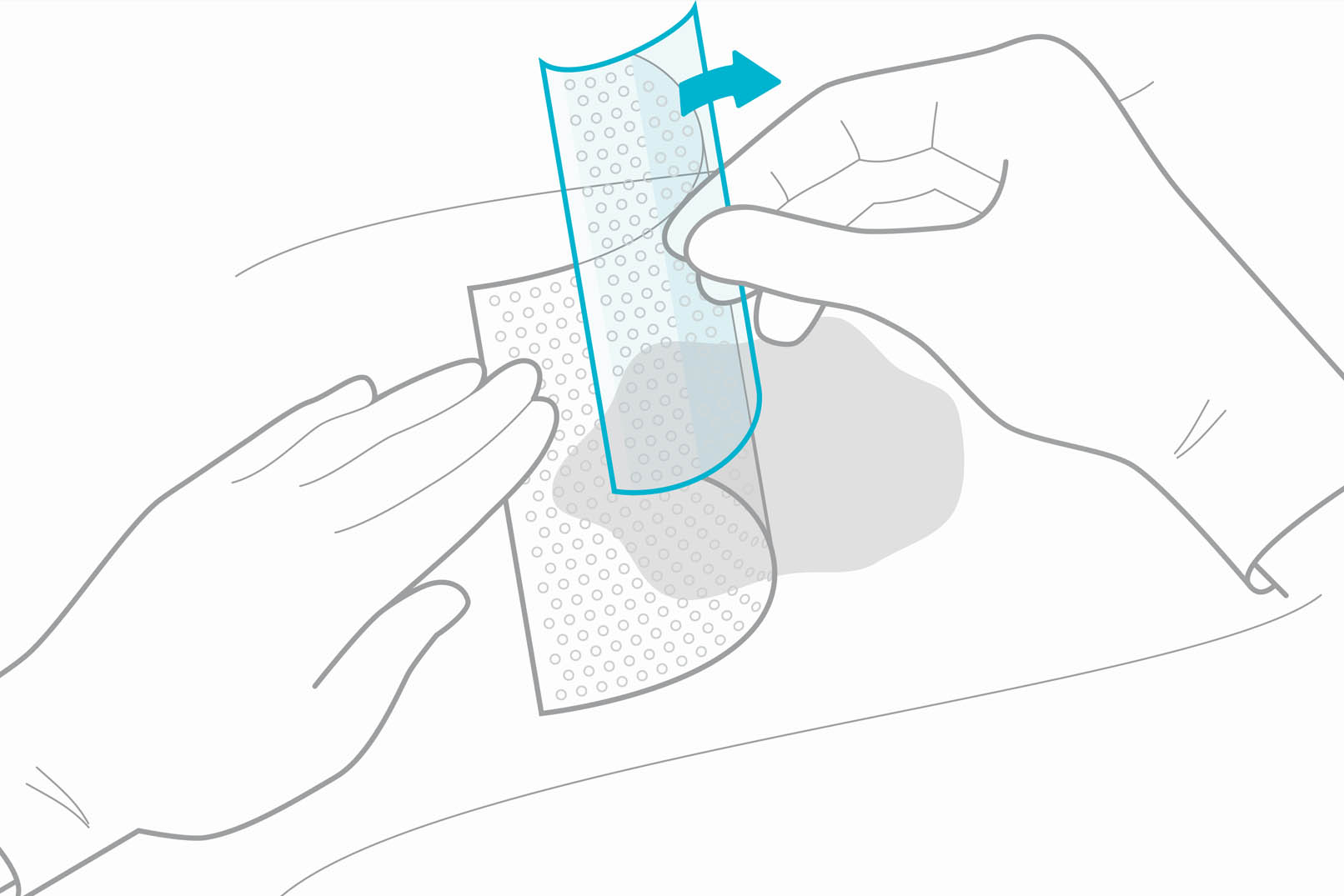

Contact Layer Dressings

Learn all about contact layer dressings, how they work and selecting the right dressing for the right wounds.

References

View References

- Adderley, U. J. (2010) Managing wound exudate and promoting healing. British Journal of Community Nurses, 15(3), 15-20.

- Baranoski, S., Ayello, E., Tomic-Canic, M. (2008). Chapter 4: Skin: An essential organ. In Baranoski, S.(Editor) and Ayello, E. (Editor). Wound Care Essentials. Practice Principles (pp. 47-63). 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Babb-Tarbox, M., Bergfeld, W. F. (2008). Chapter 11: Alopecia and Thyroid Disease. In Heymann, W. R. (editor). Thyroid Disorders with Cutaneous Manifestations (pp. 499-528). London: Springer.

- Baroni, A., Buommino, E., De Gregorio, V., Ruocco, E., Ruocco, V., Wolf, R. (2012). Structure and function of the epidermis related to barrier properties. Clinics in Dermatology, 30; 257-262.

- Beeckman, D., Schoonhoven, L., Fletcher, J., Furtado, K., Gunningberg, L., Heyman, H., Lindholm, C., Paquay, L., Verdú, J. and Defloor, T. (2007). EPUAP classification system for pressure ulcers: European reliability study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(6); 682-691.

- Black, J. M., Gray, M., Bliss, D. Z., Kennedy-Evans, K. L., Logan, S., Baharestani, M. M., Colwel, J. C., Goldberg, M. and Ratliff, C. R. (2011). MASD Part 2: Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis and Intertriginous Dermatitis. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 38(4); 359-370.

- Brown, A., Flanagan, M. (2013). Chapter 4: Assessing Skin Integrity. In M. Flanagan (Editor), Wound Healing and Skin Integrity. Principles and Practice (pp. 52-65). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Burian, E. A. (2017). Chapter 1: Huden. In B. Ø. Melby (editor), Bermark, S. (Editor). Sår og sårbehandling. En grundbog I sygeplejen (pp12-27). Copenhagen: FADL's Forlag.

- Chamlin, S. L., Tremblay, E. A. (2010). Chapter 1 You and the Skin You’re In. In Living with Skin Conditions (pp 1-13). New York: Facts on File, Inc.

- Ersser, S. J., Getligge, K., Voegeli, D. and Regan, S. (2005). A critical review of the inter-relationship between skin vulnerability and urinary incontinence and related nursing intervention. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42; 823-835.

- Grove, G. L., Zerweck, C., Pierce, E. (2002). Chapter 23: Noninvasive Instrumental Methods for Assessing Moisturizers. In Leyden, J. J. (editor), Rawlings, A. V. (editor). Skin Moisturization (pp. 499-528). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Harding, C. R., Watkinson, A., Rawlings, A. V. (2000). Dry skin, moisturization and corneodesmolysis. International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 22; 21-52.

- Janninger, C. K., Schwartz. R. A., Szepietowski, J. C., Reich, A. (2005). Intertrigo and Common Secondary Skin Infections. American Family Physician, 72 (5); 833-8.

- Johnson, A. W. (2002). Chapter 1: The Skin Moisturizer Marketplace. In Leyden, J. J. (editor), Rawlings, A. V. (editor). Skin Moisturization (pp. 1-30). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Joshi R. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:10-2

- Kennedy, R., Crowle A. (2017). Key Differences in Infant Skin. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. March 2017.

- Korting, H. C. (1990). Marchionini's Acid Mantle Concept and the Effect on the Skin Resident Flora of Washing with Skin Cleansing Agents of Different pH. In Braun-Falco, O., Flanagan, M. (Editor), Korting, H. C. (Editor). Skin Cleansing with Synthetic Detergents (pp. 87-96). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Langøen, A. and Bianchi, J. (2013). Chapter 2: Maintaining Skin Integrity. In Flanagan, M. (Editor), Wound Healing and Skin Integrity. Principles and Practice (pp. 18-32). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Lokmic, Z., Musyoka, J., Hewitson, T. D., Darby, I. A. (2012). In Jeon, K. W. International Review of cell and molecular biology, volume 296 (pp 140 - 173). Oxford: Elsevier Inc.

- Lumbers, M. (2018). Moisture-associated skin damage: cause, risk and management. British Journal of Nursing, 27 (12); 6-14.

- Mahoney, M., Rozenboom, B., Doughty, D. and Smith, H. (2011). Issues Related to Accurate Classification of Buttocks Wounds. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 38(6), 635-642.

- Martin, M. (2013). Chapter 3: Physiology of Wound Healing. In Flanagan M. (Editor), Wound Healing and Skin Integrity. Principles and Practice (pp. 33-51). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

- Muldoon (2013). Chapter 10: Chronic Ulcers of the Lower Limb. In Flanagan M. (Editor), Wound Healing and Skin Integrity. Principles and Practice (pp. 155-174). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

- Norman (2008). Chapter 12: Xerosis and Pruritus in the Elderly – Recognition and Management. In Norman, R. A (Editor), Diagnosis of Aging Skin Diseases (pp 151). London: Springer

- Paul, C. N. (2008). Skin Substitutes in Burn Care. Wounds Research, 20 (4).

- Proksch, E., Brandner, J. M. and Jensen, J-M. (2008). The skin: an indispensable barrier. Experimental Dermatology, 17; 1063-1072.

- Raschke, C. and Elsner, P. (2010). Chapter 5: Skin Aging: A Brief Summary of Characteristic Changes. In M. A. Farage, K. W. Miller and H. I. Maibach (Eds.), Textbook of Aging Skin (pp. 37-43). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Rawlings, A. W., Harding, C. R., Watkinson, A. Scott, I. R. (2002). Chapter 6: Dry and Xerotic Skin Conditions. In Leyden, J. J. (editor), Rawlings, A. V. (editor), Skin Moisturization (pp. 119-144). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Rosser, M., Couldridge G., Rosser, S. (2012). Body Massage. 3rd ed. Ocon: Bookpoint.

- Saffle, J. R., Banister, M., Cahalane, M., Lee, J. O., Palmieri, T. L. (2013). Chapter 10: Burns. In Lawrence, P. F. Essentials of General Surgery (pp. 188). 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Schmid-Wendtner, M-H., Korting, H. C. (2006). The pH of the Skin Surface and Its Impact on the Barrier Function. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 19; 296-302

- Sherwood, L. (2012). Chapter 11: The Blood and Body Defenses. In Sherwood, L. Fundamentals of Human Physiology (pp. 383). 4th ed. Belmont: Brooks/Cole.

- Shimizu, H. (2017). Chapter 1: Structure and function of the skin. In Shimizu, H. Shimizu’s Dermatology (pp 1- 42). 2nd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Shimizu, H. (2017). Chapter 15: Disorders of keratinization. In Shimizu, H. Shimizu’s Dermatology (pp 1- 42). 2nd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Sibbald, R. G., Kelley, J., Kennedy-Evans, K. L., Labrecque, C., Waters, N. (2013). A Practical approach to the Prevention and Management of Intertrigo, or Moisture-associated Skin Damage, due to Perspiration: Expert Consensus on Best Practice. Wound Care Canada, 11 (2); 1-21.

- Voegeli, D. (2012). Moisture-associated skin damage: aetiology, prevention and treatment. British Journal of Nursing, 21(9), 517-521.

- White, R. J. and Cutting, K. F. (2003). Interventions to avoid maceration of the skin and wound bed. British Journal of Nursing, 12(20), 1186-1201.

- Wickett, R. R., Visscher, M. O. (2006). Structure and function of the epidermal barrier. American Journal of Infection Control, 34, 98-110.